HPV genotyping in FFPE tissue: meeting the challenges of archival sample analysis

By Rebecca Millecamps, Fujirebio

Introduction

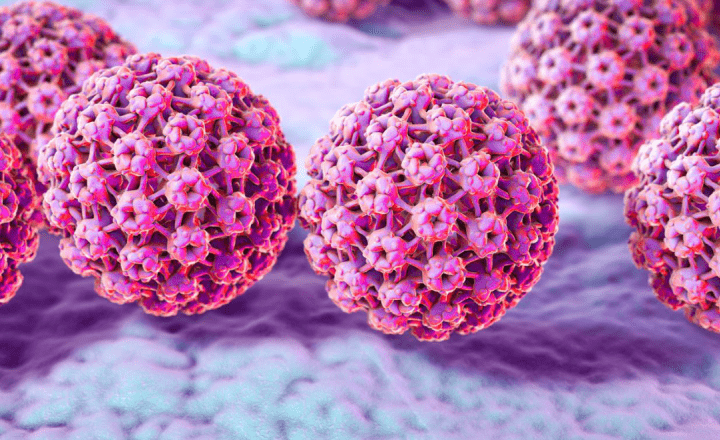

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a necessary cause of cervical cancer and is increasingly recognized as an important etiological factor in a range of anogenital and head and neck malignancies, particularly in oropharyngeal regions and oral cavity.¹ Over recent decades, prevalence and association studies have relied heavily on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens to investigate HPV genotype distribution across cervical, anal, penile, vulvar, and head and neck cancers.2-11,25-27

As HPV vaccination programs reshape the epidemiology of HPV and HPV-related diseases, genotype-specific data derived from tissue samples remain essential to inform public health policy, support vaccination impact monitoring, and guide the development of next-generation screening and triage strategies in the vaccine era. In this context, reliable HPV detection and genotyping from archival FFPE tissue continues to play a critical role. 2,4

FFPE tissue: a valuable but challenging resource

FFPE tissue represents the most widely used method of tissue preservation in pathology departments worldwide. These samples can be stored for extended periods, making them a valuable resource for retrospective epidemiology studies and research.4–13 In many clinical and research settings, FFPE tissue is the only available specimen type, particularly for historical cohorts or rare cancer types.

However, the formalin fixation and paraffin embedding process can adversely affect nucleic acid integrity. Formalin induces DNA cross-linking and fragmentation, which can compromise downstream molecular testing and increase the likelihood of false-negative or invalid results if assays are not specifically designed for degraded DNA.14

Why assay design matters for HPV testing in FFPE samples

HPV detection and genotyping in FFPE tissue is technically demanding, and assay performance is strongly influenced by the length of the amplified target region. Multiple studies have demonstrated that PCR assays targeting short fragments of the HPV genome are more sensitive and better suited to FFPE tissue-derived DNA. 4,14-18

In this context, SPF10 PCR-based methods have been consistently reported as among the most effective approaches for HPV DNA detection in FFPE samples. By amplifying a short HPV target region, these methods minimize the impact of DNA fragmentation and reduce the risk of false-negative results.4,14-18

Equally important is the inclusion of an amplifiable internal control. An internal human DNA control confirms successful DNA extraction, the absence of PCR inhibitors, and the adequacy of the sample for HPV detection. To be meaningful, the internal control amplicon should be of similar size to the HPV target.2,4

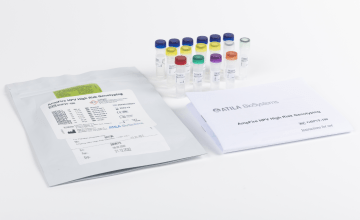

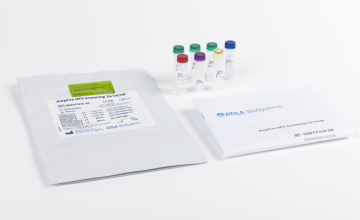

INNO-LiPA® HPV Genotyping Extra II: designed for challenging samples

INNO-LiPA® HPV Genotyping Extra II combines SPF10 PCR amplification with reverse hybridization technology, enabling sensitive and specific detection of a broad range of mucosal HPV genotypes.

Several technical features are particularly relevant for FFPE tissue analysis:

- Short amplicon design

- The SPF10 PCR amplifies a ~65 bp HPV fragment, which is well suited to fragmented DNA and supports reliable amplification from FFPE material. 4,14-18,20

- Robust internal control

- The assay includes a built-in human DNA control, comparable in size to the HPV target. This provides a reliable assessment of sample adequacy and DNA integrity in FFPE-derived extracts.13,15,17

- High analytical sensitivity

- The SPF10 PCR system enables detection of low viral load HPV infections and multiple HPV genotypes within a single sample, which is particularly relevant for FFPE tissue where viral DNA quantity may be limited.17,20

- Integrated contamination prevention

- A N-uracil glycosylase (UNG) system is incorporated to minimize amplicon carry-over and PCR contamination, significantly reducing the risk of false-positive results.4

Performance across clinical and research applications

INNO-LiPA® HPV Genotyping Extra II has demonstrated proven performance on cervical samples20 and has been successfully applied to FFPE tissue across a range of studies investigating HPV-associated disease. 2-11,25-27

Compared with other HPV genotyping methods, INNO-LiPA® HPV Genotyping Extra II has been shown to more frequently identify HPV genotypes in samples with low viral load and in FFPE material containing multiple HPV genotypes. 14-20 The small SPF10 amplicon has also enabled reliable HPV detection in other challenging sample types, including first-void urine, supporting its broader applicability in settings where DNA quality or quantity is limited.21-24

The assay can therefore support:

- Investigation of HPV prevalence and genotype distribution in different cancer types

- Evaluation of HPV vaccination trials and monitoring vaccination impact

- Epidemiological studies assessing HPV type distribution across populations

HPV genotyping in the vaccination era

As HPV vaccination programs continue to reduce the prevalence of vaccine-covered genotypes, ongoing surveillance of HPV type distribution remains essential. FFPE tissue-based studies provide a unique opportunity to assess long-term trends using existing pathology archives.

In this evolving landscape, HPV genotyping assays optimized for degraded DNA are critical to ensuring the reliability and interpretability of retrospective analyses.

Conclusion

FFPE tissue represents a cornerstone of HPV-related cancer research and pathology, but its successful use for HPV genotyping depends on carefully selected molecular methods. PCR assays targeting short HPV DNA fragments, combined with robust internal controls and contamination safeguards, are best suited to address the challenges posed by fragmented DNA.

INNO-LiPA® HPV Genotyping Extra II offers a well-established approach for HPV genotyping in FFPE tissue, supporting sensitive detection, broad genotype coverage, and reliable performance in demanding sample types. As HPV epidemiology continues to evolve in the vaccination era, such tools remain essential for research, surveillance, and public health insight.

References

- Baba SK, et al. J Transl Med. 2025 Apr 29;23(1):483.

- Stærk MG, et al. Int J Cancer. 2025 Dec 17.

- Pretet JL, et al. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:424–427.

- Kocjan B, et al. J Clin Virol. 2016;76:S88–S97.

- Sinno A, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:817–821.

- Acuña G, et al. Modern Pathology. 2019;32:621–626.

- Fuglsang K, et al. Papillomavirus Research. 2019;7:15–20.

- Valmary-Degano S, et al. Human Pathology. 2013;44:992–1002.

- Ahmadi S, et al. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:3373–3377.

- Braun SA, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021 May;35(5):1219-1225.

- Gopalani SV, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2024 Jul 1;116(7):1173-1177.

- Cabibi, D., et al. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1947.

- Donà MG, et al. BMC Cancer. 2025 Aug 7;25(1):1274.

- Steinau M, et al. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13:377–381.

- Tan SE, et al. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1458–1460.

- Querec T, et al. IPVC 2020 Book of Abstracts, pp.1013–1014.

- Bicskei B, et al. J Cancer Sci Clin Ther. 2020;4:349–364.

- Martró E. et al. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica 2012; 30 (5):225-229

- Sirera, G., et al. Sci Rep 12, 13196 (2022).

- Xu L, et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2704.

- O’Leary MC, et al. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:1221–1226.

- Ducancelle A, et al. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290:299–308.

- Jannes G, et al. EUROGIN 2018, Poster P10-5.

- Burroni E, et al. J Med Virol. 2015;87:508–515.

- Hillman R, et al. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:996–1001.

- Dalla Libera LS, et al. J Oncol. 2019;Article ID 6018269.

- Swangvaree SS, et al. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:1023–1026.