ILD diagnosis – current professional practice

By Dr. Sandra Langer, Fujirebio

Previous posts in this series:

- KL-6 in Lung Diseases: Current classification of interstitial lung diseases

- Use of serum biomarkers in progressive fibrosing ILDs

Don't miss the upcoming related Insight articles over the next weeks and get deeper information on the value of measuring KL-6 in the field of lung diseases. Or simply download the complete guidance document right away, following this link (requires a Premium eServices account).

- You will find more resources about ILDs and the KL-6 biomarker in our dedicated microsite at www.fujirebio.com/kl-6 (opens in a new window).

The role of functional testing

- HRCT scans play an essential role in the diagnosis of ILDs.

- A variety of functional tests can be used to assess severity of fibrosis, such as a measurement of forced vital capacity (FVC) and gas exchange (i.e. diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO)), and exercise capacity.

- Forced vital capacity is a reliable, valid and reproducible measure of disease progression.

- Decrease in FVC% pred. greater than 10% over a 12-month period have a significantly lower 5-year survival.

- Yet, functional tests are not specific and overlapping between different fibrosing diseases.

Accurate diagnosis of IPF is critical, as other forms of ILD that have similar clinical presentations to IPF require different treatment strategies. Imaging plays an essential role in the diagnosis of ILDs. Once known causes of ILD have been excluded, a usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) is essentially diagnostic of IPF in the appropriate clinical setting. In addition, some non-UIP HRCT patterns strongly suggest an alternative diagnosis.2

Progression of fibrosing ILDs is reflected in an increase in fibrosis evident on a computed tomography scan, a decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) and gas exchange (i.e. diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO)), worsening of symptoms and exercise capacity, and deterioration in health-related quality of life. There is no consensus as to how disease progression should be defined in patients with ILDs.

Most clinical trials and observational studies in patients with ILDs have defined disease progression in terms of decline in FVC, measured as the change from baseline in mL or as a percentage of the predicted value, as a categorical change, or as a composite of categorical change and mortality.3

Forced vital capacity (FVC) is a reliable, valid and reproducible measure of disease progression in patients with IPF and change in FVC percentage predicted (FVC% pred.) over time is a well-established predictor of mortality. Indeed, it has been shown that patients who experience a decrease in FVC% pred. greater than 10% over a 12-month period have a significantly lower 5-year survival compared to patients whose FVC% pred. declines of 10% or less during the same period of time. While there is no universally agreed upon definition for these two clinical phenotypes, they are commonly referred to as “rapid” and “slow” progressors, respectively.1

Functional tests give a good view on severity but are not specific, but common in all ILD with fibrosis.

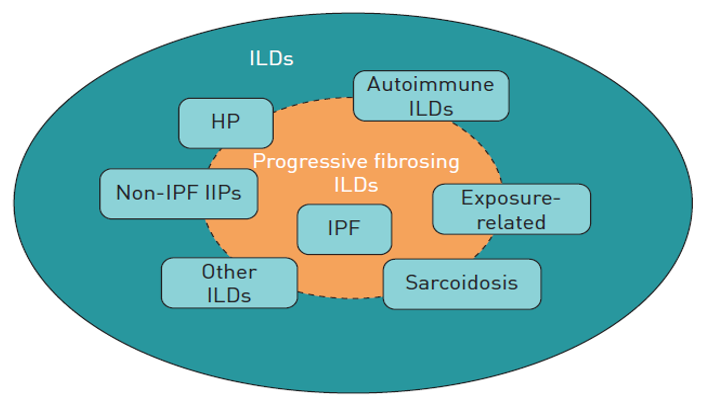

Given their overlapping clinical, radiological and pathological presentations, the terminology recently used to describe patients with fibrosing ILDs that may present a progressive phenotype, despite currently available treatment, is “progressive-fibrosing ILD (PF-ILD)”.

FIGURE 2 (from Cottin 2019 ERS Reviews): Types of interstitial lung disease (ILD) that may be associated with a progressive fibrosing phenotype. HP: hypersensitivity pneumonitis; IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; IIPs: idiopathic interstitial pneumonias.

Broader than IPF - Progressive fibrosing ILD

- Fibrosis is the common feature of a variety of different ILDs.

- Change from ILD classification related to the origin of the disease to a new way of classification in ILDs based on common features of diseases irrespective of the trigger for the fibrosis: progressive-fibrosing ILD.

- IPF as “prototype” of progressive-fibrosing ILD.

Varying proportions of patients with ILDs develop a chronic progressive-fibrosing phenotype. IPF can be viewed as the prototype progressive-fibrosing ILD; it is relatively well understood both in terms of epidemiology and disease behavior.5 In addition to IPF, fibrosing ILDs that may present a progressive phenotype include idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, connective tissue disease-associated ILDs, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, unclassifiable idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, ILDs related to other occupational exposures and sarcoïdosis.6

Whereas the current classification of ILDs is more related to the origin of the disease the question raises, if it wouldn’t make sense to use the common features of diseases for a new way of classification in ILDs to give information for possible antifibrotic treatment irrespective of the trigger for the fibrosis.

Several scientific authors deal with the idea of combining IPF with other forms of fibrosing ILD that have, i.e. self-sustaining fibrosis, progressive decline in lung function, and early mortality in the group of “progressive fibrosing ILDs” that would describe ILD in patients who, independent of the classification of the ILD, at some point in time exhibit a progressive fibrosing phenotype. This approach could be done for the purposes of clinical research and, potentially, for treatment of patients with the same symptoms regardless of the origin of the fibrotic disease. The presence of a UIP pattern also confers a worse prognosis than other patterns on HRCT in patients with IPAF and unclassifiable ILD. In a study of data from 144 patients with IPAF in a US registry, patients with a UIP pattern had similar survival to patients with IPF, while those with IPAF and patterns other than UIP had a similar survival to patients with CTD-ILDs. A greater extent of fibrosis on HRCT and worse lung function (FVC or DLCO) have also been shown to be predictors of mortality in patients with RA-ILD.3

The commonalities of ILDs that may present a progressive-fibrosing phenotype suggest the potential for a common treatment pathway.4

References

- Biondini, Davide, et al. "Pretreatment rate of decay in forced vital capacity predicts long-term response to pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis." Scientific reports 8.1 (2018): 5961.

- Chung, Jonathan H., and Jonathan G. Goldin. "Interpretation of HRCT scans in the diagnosis of IPF: improving communication between pulmonologists and radiologists." Lung 196.5 (2018): 561-567.

- Cottin, Vincent, et al. "Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: knowns and unknowns." European Respiratory Review 28.151 (2019): 180100.

- Cottin, Vincent, et al. "Presentation, diagnosis and clinical course of the spectrum of progressive-fibrosing interstitial lung diseases." European Respiratory Review 27.150 (2018): 180076.

- Olson, Amy L., et al. "The epidemiology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and interstitial lung diseases at risk of a progressive-fibrosing phenotype." European Respiratory Review 27.150 (2018): 180077.

- Richeldi, Luca, et al. "Pharmacological management of progressive-fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: a review of the current evidence." European Respiratory Review 27.150 (2018): 180074.

Don't miss the next posts on this topic in the following weeks:

You might also find this website interesting:

- You will find more resources about ILDs and the KL-6 biomarker in our dedicated microsite at www.fujirebio.com/kl-6 (opens in a new window).